For patents that survive IPR, this means that the district court proceedings effectively start after 2.5 years. Accordingly, if a Court grants a stay of patent litigation upon the filing of an institution decision, a case may be stayed for 2.5 years or longer (six months for the institution decision, followed by one year to the final determination, followed by another year for an appeal). While the PTAB is statutorily required to render a final decision in most instances within one year after instituting an IPR, the final decision is most commonly followed by an appeal to the Federal Circuit by the losing party, which may take a year or longer to resolve. If a stay is granted, no further action in the case occurs until there is a final determination from the PTAB, and often, until any appeals of that final PTAB determination are resolved. After filing an IPR petition, however, defendants usually file a motion in district court to stay patent litigation. There is no rule requiring that patent litigation pending before a district court be stayed based on either the filing of an IPR or the institution of an IPR. The remainder of final determinations resulted in mixed determinations, with at least one claim being found unpatentable, but others upheld or in amendments to the claims. Of these recent final determinations, only 18% resulted in a determination confirming the patentability of all challenged claims in favor of a patent owner. Of those IPRs that were instituted and that had reached a final determination as of this post, over 60% resulted in a final determination that all claims are unpatentable in favor of the challenger. For the approximately 1800 IPR petitions filed after Januin which the PTAB issued an institution decision, 72% of those petitions to institute IPR were granted, and the IPR instituted. Recent statistics continue to confirm the effectiveness of IPRs for patent challengers.

An IPR is instituted if “there is a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail with respect to at least 1 of the claims challenged in the petition.” 35 U.S.C. The PTAB is statutorily obligated to decide whether or not to institute an IPR within six months of a petition’s filing date, 35 U.S.C. IPRs begin with the filing of a petition for institution of PTAB review by a patent challenger. IPRs increase the costs of patent litigation for everyone involved-as the proceeding is akin to a mini-trial-but given the statistics associated with IPRs, there are few real drawbacks to defendants for filing such proceedings. IPRs tend to result in the cancellation of many patents, and relatively few patent cases proceed without any IPR challenge. Defendants also choose whether to request that a court stay patent litigation pending a decision on their IPR petition, or if the IPR is instituted, pending the PTAB’s final determination on a petition. Defendants choose whether and when to file an IPR petition, although such a petition must be filed one year before the date on which a defendant is served a complaint. Generally, while a patent owner plaintiff controls where a case is filed, defendants drive the timeline of a case through a variety of procedural mechanisms, including IPRs.

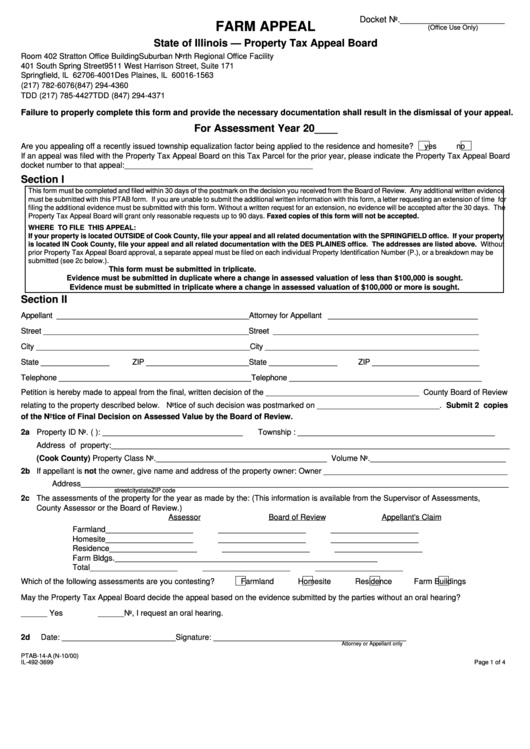

VIEW PTAB FILED DOCUMENTS TRIAL

Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent and Trial Appeal Board (“PTAB”), seeking review of whether a patent should have been issued. An IPR is a parallel challenge that an accused infringer may file in the U.S. Even before COVID derailed many patent trials, patent cases were often stayed-or procedurally paused-pending a proceeding called inter partes review (“IPR”). Such disruptions in the timelines of cases are not new to patent litigators, however. COVID hampered in-person discovery and caused courts to re-set jury trial dates. Over the course of the past year, many trial attorneys in state and federal courts have seen cases effectively stayed by COVID-related delays.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)